I’ve never read manga before: Where do I start?

If you are just starting to explore manga for the first time, you might be intimidated by the sheer number of titles available to read, as well as the terminology used to categorize and describe them. If that is the case for you, let this post serve as your Beginner’s Guide to Manga. I will define some common manga terminology, explore some of its history, and leave you with some recommendations from various genres.

What is Manga?

First of all, let’s define manga. Manga is a Japanese word that refers to comics and cartooning. In the rest of world, it typically refers only to comics and graphic novels that were originally created and published in Japan. This is similar to anime, which is used in Japan to describe all animated content, but specifically refers to Japanese animated content when used by the rest of the world. (Although this point is increasingly up for debate with the rise of global streaming platforms producing original “anime-style” shows. More on that in a later blog post.) Unlike American comic books, which are generally released monthly in single issues, manga in Japan is usually published in weekly or monthly magazines like Weekly Shōnen Jump, which contain single chapters of many ongoing series. When a series gets popular, these chapters will get collected and sold as a volume.

Another major difference is that manga is read right to left, whereas American comics (and almost everything else written in English) are read left to right. You might think that this is because Japanese is read right to left, like Arabic. Well… it’s actually more complicated than that. Rebecca Shiraishi-Miles wrote a great breakdown of Japanese reading direction for Team Japan. To summarize her article, Japanese has two writing formats: tategaki (縦書き) and yokogaki (横書き). Tategaki is used for traditional Japanese writing, and is written vertically and read top to bottom, right to left. This is the style of writing used in most manga. However, modern Japanese can also be written horizontally. This writing format is yokogaki, and it is read left to right, just like English.

So, why is manga still read right to left when it is translated into English? This hasn’t always been a standard publication practice. Some older series, like Ōtomo Katsuhiro’s Akira, were published left to right when released in English in order to be more accessible to American audiences. Although this seems like a logical decision, there is a major downside: the artwork will suffer. The artwork was originally drawn to flow with the writing, from right to left. Reversing the reading order of the book requires the artwork to either be altered (which is expensive and time-consuming) or to be stuck fighting the flow of the words. It may take some getting used to, but reading manga right to left helps retain the creator’s vision and provide a better visual experience.

One more difference between manga and American comics is that manga is printed in black and white, not full color. Although there will often be a couple full-color pages in a manga magazine or volume, most of the story is black and white. This is because it is cheaper and faster to produce. Manga creators often have extremely tight production schedules, like the one outlined in this Anime Art Magazine article, and don’t have the time or resources to include full color. While they do have assistants to finish drawing panels, there is no dedicated colorist like there is on American comic book production teams.

Manga Terminology

Before we get into some history, here are a few terms that are useful to know when discussing manga.

Mangaka – The creator of a manga series. They are commonly both the writer and artist, though not always.

The next few terms refer to audience demographics, but they are often discussed as if they are genres. This is because manga is generally created for a specific age and gender demographic, and these series in each of these categories tend to share certain attributes, despite encompassing a wide variety of genres.

Shōnen (also romanized as shonen or shounen) – Marketed to young boys. Some of the most popular manga series of all time, including Dragon Ball and Naruto, are examples of shōnen.

Shōjo (also romanized as shojo or shoujo) – Marketed to young girls. Popular examples include Sailor Moon and Fruits Basket.

Seinen – Marketed to adult men. Popular examples include Akira and Neon Genesis Evangelion.

Josei – Marketed to adult women. Popular examples include Princess Jellyfish and Paradise Kiss.

While manga is categorized by demographic, it can also be sorted by genre. Most of these genres are the same common ones you would find in books, movies, and television (i.e. action, adventure, romance, sports), but there are a few genre terms you may be unfamiliar with.

Isekai – Literally “different world.” Refers to stories in which the protagonist ends up in a different (usually fantasy) world, and is often an adventure, comedy, or romance. Popular examples include The Rising of the Shield Hero and That Time I Got Reincarnated as a Slime.

Gekiga – literally “dramatic pictures.” Refers to adult stories with darker themes and more realistic art styles. Popular examples include Lone Wolf and Cub and Kamui.

Boys’ Love (commonly shortened to BL) – While this term is not used exclusively for Japanese manga, it is a popular genre showing romance between male protagonists. This term is starting to grow more popular than the overly fetishized “yaoi,” which is an acronym of yama nashi, ochi nashi, imi nashi or (roughly) “no climax, no point, no meaning,” which referred to the genre’s early emphasis on sex over romance. Popular examples of Boys’ Love include Given and I Hear the Sunspot.

Yuri – literally “lily,” it refers to depictions of romance between female protagonists. This genre is also commonly marketed as Girls’ Love (commonly shortened to GL) to mirror the Boys’ Love genre, but the term yuri does not have the same fetishized history as yaoi, so it is not seen as inappropriate to use. Popular examples include Bloom Into You and Whispered Words.

A Brief History of Manga

I am by no means an expert in Japanese history (or art history), so although I will try my best to summarize the origins of manga and its growth into the cultural and artistic powerhouse it is today, I encourage anyone interested in the subject to do further research. Most of the information I will use here comes from Brigitte Koyama-Richard’s book One Thousand Years of Manga, which is an excellent place to start for anyone looking for a more in-depth discussion of manga history.

While the exact origins of manga are unknown, it is a continuation of a long history of Japanese narrative art dating back to the eighth century and beyond. Illuminated scrolls from this time period have narratives that are revealed as they are unraveled, which imitates the flow of time later represented in manga through the use of sequential panels. Some specific examples of scrolls that uses manga-like attributes are the Shigisan Engi Emaki (信貴山縁起絵巻, lit. “Legend of Mount Shigi Emaki”) and the Chōjū-jinbutsu-giga (鳥獣人物戯画, lit. “Animal-person Caricatures”). The Chōjū-jinbutsu-giga, attributed to the monk Toba Sōjō, with its satirical portrayal of animals, would prove to be especially influential thanks to its style gaining a resurgence in popularity during the Edo period (1603-1867). In addition to combining art and lettering, the artists of these works drew a character’s legs to simulate running in a technique that is still used by manga artists today (Widewalls, “A Short History of Manga”).

Japan’s art and printing culture experienced huge transformations during the Edo period. Ukiyo-e art was circulated heavily thanks to woodblock printing techniques, and art became more accessible to the public. Advances in printing also spurred an increase in book publishing, and various types of books became popular. Collections of Toba-e prints, which imitated the style of works such as the previously mentioned Chōjū-jinbutsu-giga, were particularly popular. These collections serve as a precursor to comic-style books.

The first use of the term manga referred to the picture book Shiji no Yukikai (Four Seasons) by Santō Kyōden in 1798 (Widewalls, “A Short History of Manga”). It was later used in the titles of two 1814 books: Aikawa Mina’s Manga hyakujo and Katsushika Hokusai’s Hokusai Manga, which were both collections of illustrations. Despite this early use of the term, it was not widely used until much later. The terms “giga” and “Toba-e” were used instead, referring to caricatures or cartoons.

During the Meiji era (1868-1912), caricatures and comics inspired by Western influences started showing up in newspapers and journals. These were commonly referred to as “ponchi-e.” These developed into the Japanese comic strip, pioneered by Kitazawa Rakuten. He combined traditional Japanese art styles with Western techniques and influences, and began calling his comics manga.

This fusion of Japanese and Western art was accelerated during the post-World War II occupation of Japan by the United States. American soldiers brought comics and cartoons from home, including Disney’s iconic Mickey Mouse. These comics inspired Japanese artists, who then developed their own unique styles. One such artist is Tezuka Osamu, who is known as the “God of Manga” for his influence on the modern manga industry. He is the creator of the wildly popular Astro Boy, as well as many other beloved series, and the influence of his art style on the industry can still be seen today.

In addition to being one of the earliest commercially successful manga series in Japan, Astro Boy was also the earliest manga series to be adapted and brought to the United States. While the growth of the North American manga industry started out fairly slow, VIZ Media (a subsidiary of the Japanese publishers Shōgakukan and Shueisha) continued to distribute translations of manga series throughout the 1980s and 1990s. In 1998, a colorized version of Ōtomo Katsuhiro’s Akira produced by Epic Comics was the first manga to make it big in the United States.

In the early 2000s, American publishers began releasing anthologies, including an American version of Japan’s most popular manga magazine, Shōnen Jump, which included series such as Dragon Ball Z, Naruto, Bleach, and One Piece. The presence of manga in big bookstore chains such as Borders and Barnes & Noble helped increase its visibility and popularity, and the rising popularity of anime on American television channels has helped draw attention to the original manga series that serve as its source material. Perhaps the most influential factor in manga’s incredible popularity in the United States today, however, is the internet. Between anime’s large presence on streaming services, social media fostering discussions of anime and manga (as well as showcasing cosplays and fanart), and the availability of digital versions of manga, it is incredibly easy to find and enjoy manga in the United States and around the world.

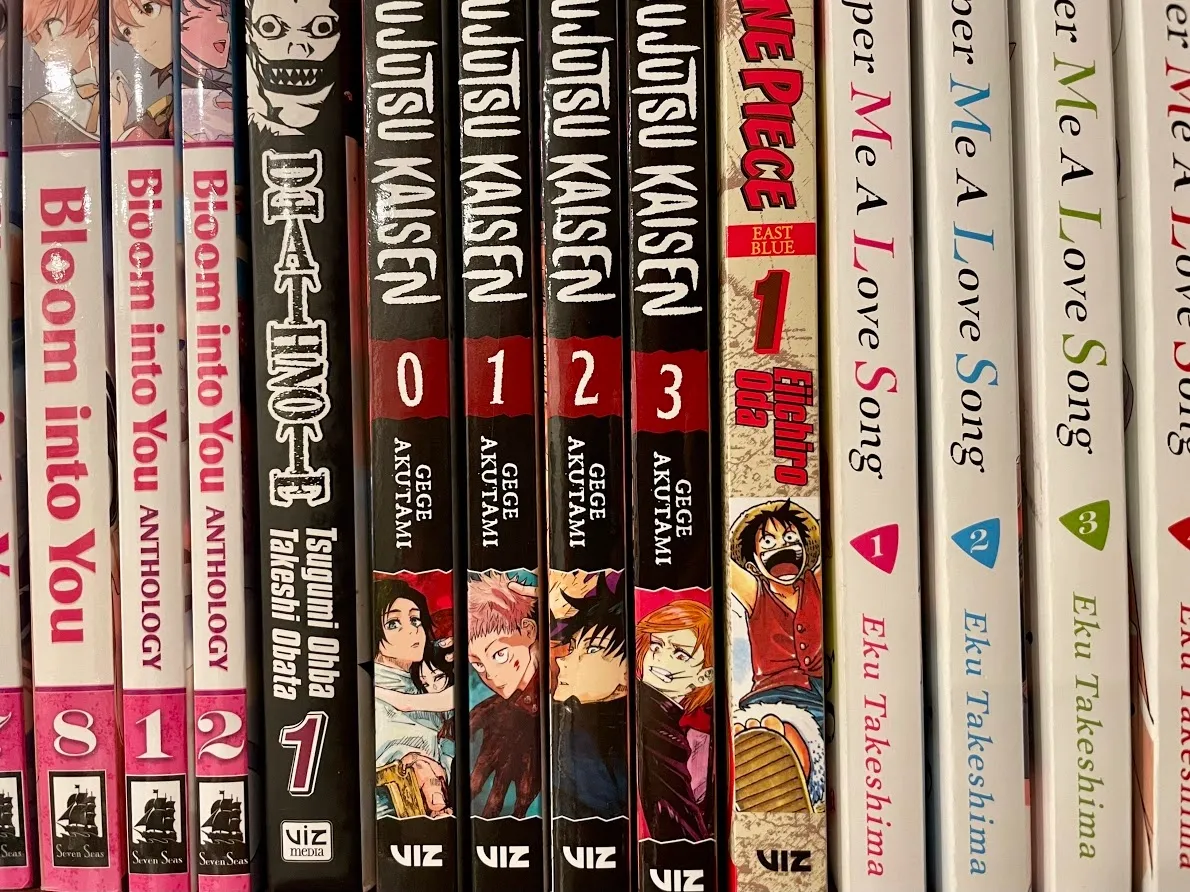

Recommendations

Now that you know some manga terminology and history, you’re ready to start reading! Here are some recommendations to get you started, separated by demographic (though I encourage you to read series from all different demographics and genres).

Shōnen

Arakawa Hiromu’s Fullmetal Alchemist – This popular science fiction adventure series is the basis for both the Fullmetal Alchemist and Fullmetal Alchemist: Brotherhood anime series. It follows brothers Edward and Alphonse Elric on their journey to restore their bodies after an attempt to bring their mother back to life with alchemy goes horribly wrong. Along the way, they meet a variety of complex characters and uncover a dark conspiracy in their country’s government. Along with a simple yet interesting magic system, Arakawa manages to blend darker themes with lighter comedic moments while examining deep philosophical and moral questions.

Eiichirō Oda’s One Piece – This long-running pirate adventure series is beloved by fans around the world and is a masterpiece of worldbuilding. While the 102 (and counting) volumes are intimidating for new readers, the adventures of Monkey D. Luffy and his crew will have you hooked from the beginning and will keep you entertained for a very long time.

Shōjo

Takeuchi Naoko’s Sailor Moon – The characters of Sailor Moon are instantly recognizable, and the anime adaptation captured the attention of girls around the world. This iconic magical girl series stars schoolgirl Usagi Tsukino and her comrades, who transform into Sailor Guardians to fight villains and protect the solar system. The high-quality art, fun combat scenes, and focus on female empowerment make this a great choice for anyone looking to enjoy shōjo manga for the first time.

Takaya Natsuki’s Fruits Basket – This supernatural romantic comedy follows protagonist Tohru Honda as she uncovers the truth about the Sohma family, who are possessed by (and cursed to turn into) the animals of the Chinese zodiac. The expressive artwork and gradually intensifying themes helped make it one of the most popular shōjo manga in both Japan and the United States.

Seinen

Ōtomo Katsuhiro’s Akira – This post-apocalyptic cyberpunk series was one of the first manga series to grab the attention of American audiences, and it is a great place to start for anyone new to seinen manga. Set in a futuristic “Neo-Tokyo” destroyed by a mysterious explosion, the series features a complex cast of characters, many with strange supernatural abilities, trying to prevent a mysterious entity with psychic powers from being awoken. With its darker themes and gritty storytelling, it tells a compelling story that appeals to a more mature audience.

Sadamoto Yoshiyuki’s Neon Genesis Evangelion – Unlike most of the series I have recommended thus far, Neon Genesis Evangelion is not actually the source material for the anime series of the same name (although it did come out first). The story–which follows a teenage boy named Shinji Ikari, who is recruited to pilot a mecha named “Evangelion” in the fight against beings called “Angels”–was originally planned as an anime series with the manga to serve as a companion adaptation, but production delays caused the manga to be released first. Despite not being an original story, this manga became a commercial success and serves as a solid example of seinen manga.

Josei

Higashimura Akiko’s Princess Jellyfish – Set in an all-female occupied apartment building where men are banned from entering, this coming-of-age romantic comedy focuses on Tsukimi Kurashita, an aspiring illustrator fixated on jellyfish. She discovers one of the other women is actually a man who cross-dresses in order to escape politics and feel closer to his mother, and agrees to keep his secret. This heartfelt story explores relatable themes and is a nice introduction to josei manga.

Fujita’s Wotakoi: Love Is Hard for Otaku – Originally a webmanga, this romantic comedy between two geeky office workers became so popular it is now printed in physical volumes and has been adapted into an anime. It has pleasing art and a wholesome story showcasing the difficulty of balancing work, romance, and hobbies.

Now that you have some background knowledge on manga and some recommendations for where to start, you’re ready to begin your manga reading journey. Thank you for reading Mythic Fox’s very first blog post, and be sure to come back for more. Happy reading!